New research shows how increasingly intense solar flares could disrupt the GPS satellite connections that have made Kansas farms more efficient.

HAYS — Kansas farmers battered by drought and heat now have more weather to worry about — in outer space.

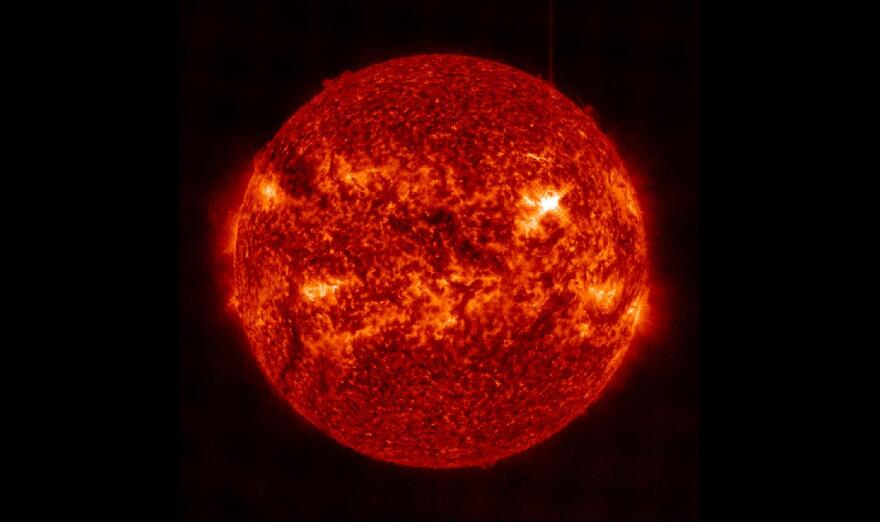

An expected surge in solar flares over the next several years will likely send massive bursts of radiation hurtling toward our atmosphere. And that would threaten satellite signals.

That matters to farmers because much of the technology that has made modern farms increasingly efficient relies on those satellites, particularly global positioning systems, or GPS.

So even just a short time without GPS could come with a steep cost for Midwestern farmers.

“It could be, easily, a billion-dollar loss of efficiency even for two days,” Kansas State University agricultural economist Terry Griffin said. “The likelihood of that occurring is fairly good enough to where really smart people are concerned about it.”

A new study from Griffin and a team of other researchers from institutions such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Space Weather Prediction Center came up with that $1 billion figure based on a potential widespread GPS outage that would hit farming at a critical time — such as corn planting season in the spring — across the Midwest.

On a smaller scale, solar energy from 90 million miles away already degrades satellite signals on a regular basis.

Weston McCary, technology projects coordinator for the Kansas Water Office based in Colby, Kansas, said he has commonly seen solar radiation disable satellites for 20 minutes to an hour.

“These systems are vulnerable to this solar activity,” McCary said. “It’s not if. It’s when.”

A geomagnetic storm in our atmosphere caused by a solar flare took out 40 Starlink satellites earlier this year. Increased solar activity this summer has sped the downfall of some European Space Agency satellites.

And as scientists expect solar activity to ramp up in the coming years, those outages could become longer and more frequent.

“You can’t predict if it’s going to be 20 minutes or 20 days,” McCary said. “(But) we should expect it to happen, because it’s just fact.”

Staring at the sun

So why are experts worried about space weather impacting farm technology now? Timing.

Centuries of astronomical records show that solar flares happen in a cyclical pattern, with the intensity and frequency peaking roughly every 11 years.

Solar activity is now ramping up toward its next peak. And the current solar cycle is already looking more intense than the previous 11-year period.

The other piece of timing that concerns experts is how much more GPS has been integrated into the lives of farmers — and people in general — since the last time solar activity peaked several years ago.

More than two-thirds of Kansas grain farms now use GPS to steer their tractors. That helps farmers plant expensive seed in exact rows without unintentionally overlapping them.

About half of farms use GPS to map their harvest yields, which gives them valuable data about what they should plant in future seasons. Another quarter of farms use GPS mapping to pinpoint the amount of fertilizer they apply to each part of their land.

And the loss of those efficient practices multiplied across hundreds of thousands of Midwestern farms would quickly add up.

“When you’re looking at how much money goes into an ag operation on a daily basis,” McCary said, “when the wheels stop turning, things get expensive real fast.”

Integrating GPS into farming isn’t a bad thing, McCary said. It’s an essential element of the precision agriculture movement — farmers using satellite guidance, data and maps to conserve resources and save money. GPS can also help western Kansas farmers avoid wasting water from the dwindling Ogallala Aquifer when they irrigate.

But the more integrated technology becomes with farming, the more the sudden loss of that technology would hurt.

“Could it still be done manually? Absolutely,” McCary said. “Would it be as efficient? No. Would it cost us some money as an economy of scale? Absolutely.”

Plan B

Agriculture wouldn’t be the only part of life impacted by this type of celestial event. If GPS goes down on the farm, chances are it’ll go down in people’s cars too. It could even potentially disable cell phones and power grids.

And satellites’ impact on the farm goes well beyond GPS-guided tractors.

The U.S. agriculture industry relies on the overhead photos they take of cropland to assess the impact of insects and drought. Ranchers can use collars fitted with transmitters and sensors to track their livestock’s movements. Some farmers in remote areas without broadband depend on satellites for their internet connection.

But even in a worst-case scenario where farmers lose access to GPS for a long period, McCary said, it doesn’t mean agriculture would automatically go back to the stone age.

He’s optimistic that farmers could fall back on ground-based radio positioning technology they used a couple of decades ago. Or just eyeball it.

“That’s how we’ve been planting corn for the better part of 100 years,” McCary said. “So the average farmer, especially the older gentlemen … they would have no problem getting right back out there.”

But the reality is that a lot of people — not just farmers — aren’t even aware of the possibility of a cosmic event disrupting the technology they’ve grown to depend on.

Griffin, the K-State farm economist, has traveled the state talking with farmers about this issue for more than a decade. He said most folks are hearing about it for the first time. But farmers have been receptive when he presents the science, he said, so there’s some momentum for building awareness.

The first step for farmers, Griffin said, is to figure out how they could keep their operation running temporarily without GPS so they aren’t caught off guard. Maybe talk with their financial advisors and equipment dealers to discuss back-up options.

It’s like keeping a spare tire and jack in the back of your car. Even if you don’t anticipate getting a flat tire each time you go for a drive, you know it’ll happen eventually. And when it does, you want to be ready.

“We cannot control solar activity as humans,” Griffin said. “But what we can do is try to make a plan.”

David Condos covers western Kansas for High Plains Public Radio and the Kansas News Service. You can follow him on Twitter @davidcondos.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of High Plains Public Radio, Kansas Public Radio, KCUR and KMUW focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.

Don’t miss a beat … Click here to sign up for our email newsletters

Click here to learn more about our newsletters first

Latest state news:

Kansas champions of administrative reform at public universities offer concessions to calm skeptics

The Republican majority leader of the Kansas House and the governor’s chief of staff worked Thursday to resolve objections to a bill designed to make the state’s three largest public universities more financially efficient by removing layers of administrative red tape.