Educators tout social-emotional learning as a way to make children into better students and more empathetic people. Critics see it as a way to push social justice issues.

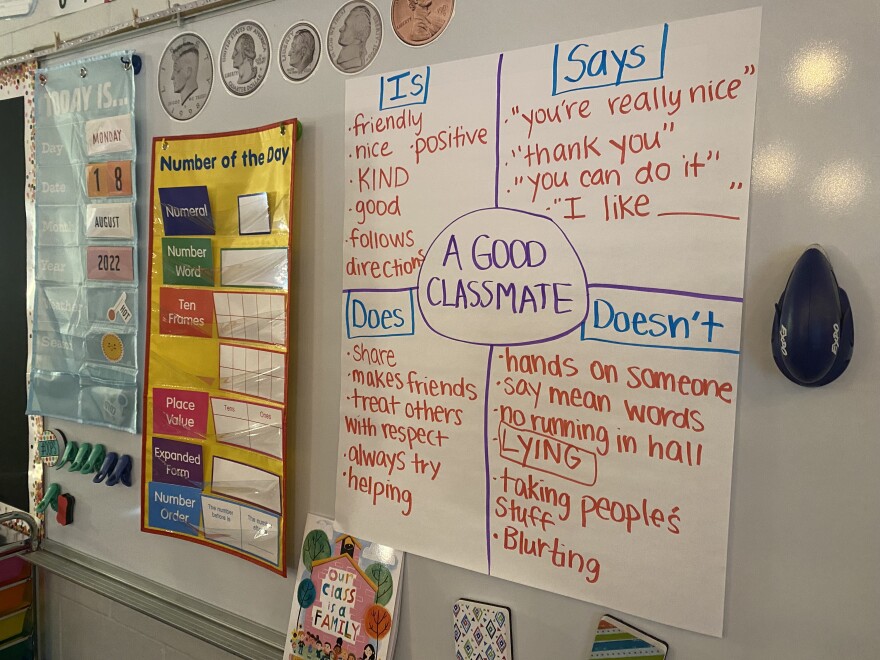

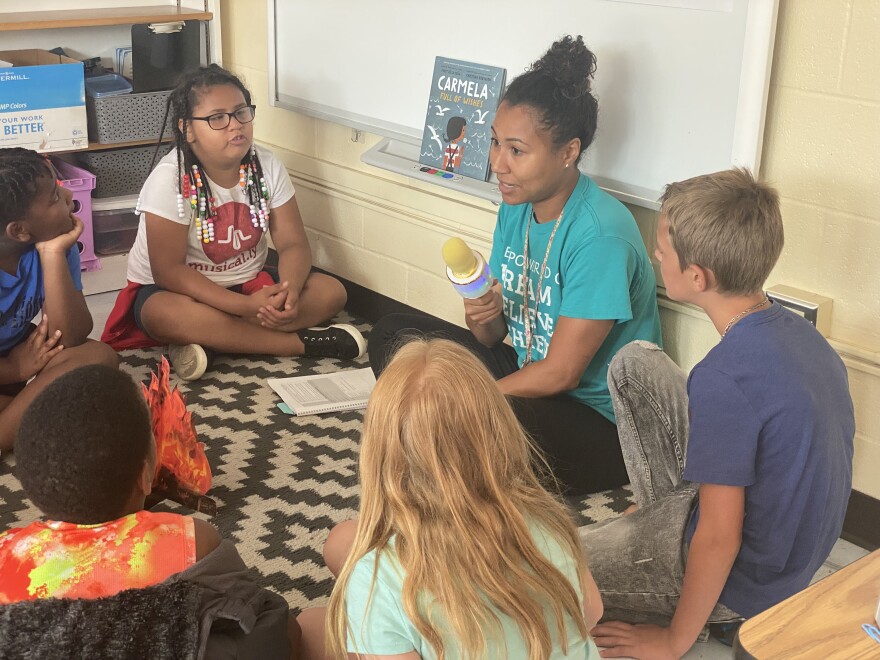

WICHITA — On the first day of school at Enterprise Elementary, Kasey Curmode gathered her second-graders on the carpet and posed a question: “What makes a good classmate?”

Someone who shares, one student said.

Someone who says, ‘You’re really nice,’ said another child, or ‘You can do it!’

Someone who doesn’t lie, or say mean words, or take other people’s stuff.

Curmode’s first lesson of the day — and of the school year — focused on feelings.

“It really helps these students … get into a positive mindset,” she said. “Some of them don’t know how to regulate their emotions. So even 20 minutes a day is going to help them tremendously.”

Social-emotional learning — often referred to by its acronym, SEL — existed in Kansas classrooms ever since the one-room schoolhouse. Teachers have long encouraged children to try hard, set goals, control their anger and treat others with respect.

But now it’s an explicit thing for teachers to teach. Social-emotional growth is one of five priorities for the Kansas Department of Education and included as part of the standards the state uses to measure students and schools.

It’s also the latest flash point in the classroom culture wars. Schools — their teachers, their administrators, the companies that sell them pre-made lesson plans — see SEL as a smart and nurturing way to make kids more empathetic and resilient. The same curriculum strikes conservatives as a back-door way for secularists to promote gay rights, racial guilt and something that blurs fundamental differences between boys and girls.

Conservatives took control of two seats on the Kansas Board of Education this month, in part by saying schools should focus on basic academics and leave the social and emotional upbringing to parents.

“A lot of people are concerned about indoctrination instead of education,” said Dennis Hershberger, who ousted incumbent Ben Jones in the Republican primary and is unchallenged in November. “Teachers … deal with things in the classroom that are much more about creating a society that most parents don’t agree with.”

Cathy Hopkins, who beat incumbent Jean Clifford in western Kansas, said on her campaign website that she wants to “protect our children from liberal education standards handed down to our schools by Washington, D.C., liberals” and to “return our local schools back to academics.”

Hershberger and Hopkins say social-emotional learning in public schools should be opt-in, meaning it would be taught only to students whose parents specifically OK it. They also oppose surveys, for instance, that ask students about their personal relationships or mental health.

During a recent Kansas Board of Education meeting, board member Michelle Dombrowsky voiced concerns about some SEL materials and reminded parents that they have the right to opt their children out of any activity that goes against their personal beliefs.

“Whether it be suicide awareness — I may take them for ice cream that day. They’re not going to be involved in that,” Dombrowsky said. “If it’s somebody coming in from the outside and discussing that. … Sometimes, if they’re young enough, it’s putting things in their mind.”

Earlier this year in the Kansas Legislature, some supporters of a proposed Parents’ Bill of Rights said classroom lessons are being “weaponized” and that social-emotional and diversity programs are training young children to become activists.

Child psychologists and experts in social and emotional learning say it’s being misunderstood.

“If you ask a parent, ‘Would you like your child to work well with others? Would you like them to develop strong communication skills? Have employability skills?’ … The answer, unequivocally, is yes,” said Jessica Lane, a specialist in education counseling at Kansas State University. “It’s just that the terminology has, for whatever reason, sparked a lot of controversy.”

Wichita, the state’s largest school district, spends about $100,000 a year for a program called Second Step for students in kindergarten through eighth grade.

Lessons for young students feature posters, songs, and hand-puppets like Slow-Down Snail, who encourages children to pause and take a breath if they feel angry or upset. Older students learn to recognize symptoms of depression and how to deal with test-related anxiety.

A school district in Utah suspended its Second Step program last fall, following pushback from parents who said schools were teaching objectionable material about sex.

The parents said Second Step had pointed middle-schoolers to a website, loveisrespect.org, which offers information about dating and sex. Pop-up windows on the website tell visitors how to quickly exit the site and clear their browsing histories, which opponents said was an affront to parental oversight.

Counselors and social workers say lessons on consent and domestic abuse are important for older adolescents. But the bulk of social-emotional programs focus on basic character building that has nothing to do with sex.

Erin Yosai, director of the Center of Psychoeducational Services at the University of Kansas, says more than 20 years of research shows that students who feel safe and learn self-control not only behave better in the classroom — they also get higher grades and test scores.

“Our reading, our writing, our arithmetic, all of our other subjects are impacted and interrelated with our ability to have positive social experiences, knowing how to regulate ourselves in different areas,” she said.

A study published in 2015 showed that boosting social skills in kindergarten can predict a child’s success more than 20 years later. Children with more developed social and emotional skills had better attendance and were more likely to graduate from high school on time and to earn a college degree.

“The fact that people are saying you can extricate (social-emotional learning) from academics – really, we wouldn’t want to,” Yosai said. “These two things go hand in hand.”

Suzanne Perez reports on education for KMUW in Wichita and the Kansas News Service. You can follow her on Twitter @SuzPerezICT.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.

Don’t miss a beat … Click here to sign up for our email newsletters

Click here to learn more about our newsletters first